Britain’s Nuclear Deterrent Development – Part Three

(A sign outside the Manhattan Project building in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, in 1943)

The BNTVA have been allowed to use this blog with kind permission from the Vulcan to the Sky Trust www.vulcantothesky.org

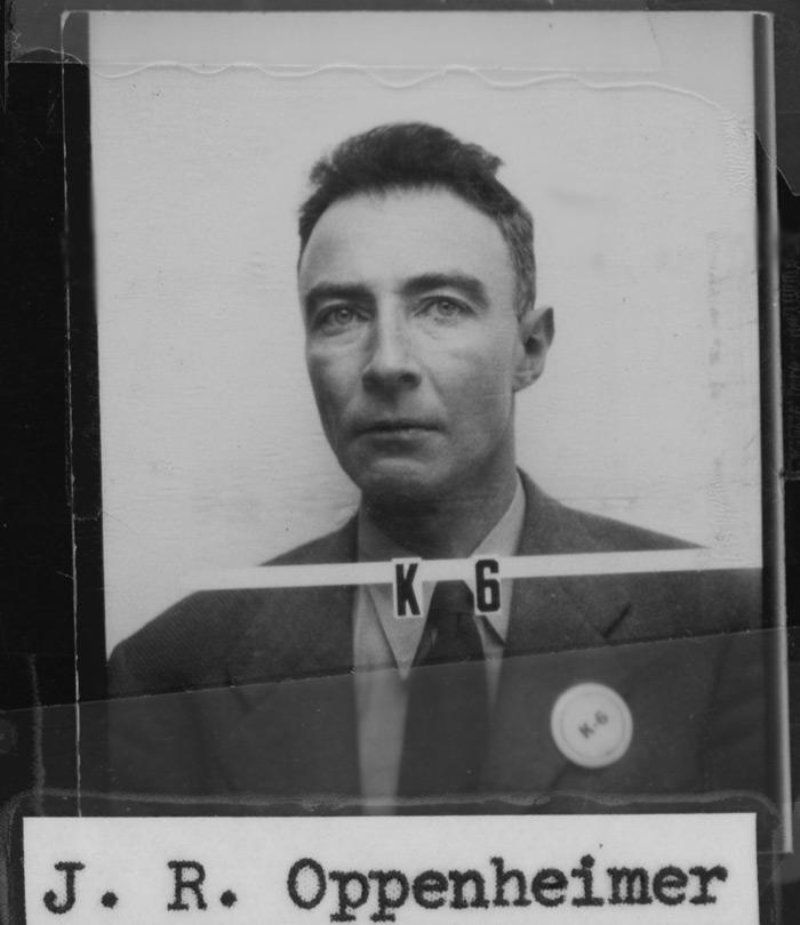

(J.R. Oppenheimer’s Los Alamos ID photo c.1943)

Julius Robert Oppenheimer was an American theoretical physicist and is among those who are credited with being the “father of the atomic bomb”. He was the head of the Los Alamos Laboratory, which was to be the Manhattan Project’s secret weapons laboratory. Oppenheimer was selected for the role by Brigadier General Leslie R. Groves, Jr., the director of the Manhattan Project.

For security, Oppenheimer and Groves needed a centralised, secret research laboratory in a remote location. The site chosen by them was a private boys’ school called the Los Alamos Ranch School. In November 1942 the school and surrounding land were bought by the United States Army’s Manhattan Engineering District, and converted into the secret nuclear research campus also known as Project Y.

In early 1943, after an assessment of developments, Oppenheimer determined that two projects should proceed forwards. He chose the ‘Thin Man’ project (plutonium gun) and the ‘Fat Man’ project (plutonium implosion). The gun-type weapon was to receive the bulk of the research effort, as it was the project with the least uncertainty.

The code names were created by Robert Serber, a former student of Oppenheimer’s who worked on the Manhattan Project. He chose them based on their design shapes. The ‘Thin Man’ would be a very long device, and the ‘Fat Man’ bomb would be round and fat. It’s also suggested that the shapes mirrored the US President Roosevelt (Thin Man) and the UK Prime Minister Winston Churchill (Fat Man).

The Hanford site in south-central Washington was established in 1943 as part of the Manhattan Project. The site was to be home to the B Reactor, which began functioning in September 1944 and was the first full-scale plutonium production reactor in the world. The reactor was to produce plutonium-239 by neutron activation. Plutonium-239 would be used for the production of the nuclear weapons.

19 August 1943 – The Quebec Agreement stipulated that the United Kingdom and the US would pool resources to develop nuclear weapons. The agreement merged the British Tube Alloys project with the American Manhattan Project, and created the Combined Policy Committee to control the joint project.

After the signing of the Agreement, James Chadwick and the team of prominent British scientists who had been working on the Tube Alloys project, transferred to the United States to contribute to the Manhattan Project. The scientists included William Penney, Rudolf Peierls, Klaus Fuchs and Mark Oliphant.

Brigadier General Leslie R. Groves, Jr. originally disapproved of the collaboration. He put the British scientists in limited roles to restrict their access to complete information. The text of the Quebec Agreement was vague in places, with loopholes that Groves could exploit to enforce this compartmentalisation.

Chadwick, Peierls and Oliphant were important enough that the bomb design team at the Los Alamos Laboratory needed them. Chadwick was in no doubt that the first duty of the British was to assist the Americans with their project and abandon all ideas of a wartime project in England. Before the end of 1943 the three had taken up indefinite residence in America.

In September 1943, Groves and Oppenheimer revealed the existence of the Los Alamos Laboratory to the three British. Oppenheimer wanted all three to proceed to Los Alamos as soon as possible, but it was decided that Oliphant would go to Berkeley to work on the electromagnetic process and Peierls would go to New York to work on the gaseous diffusion process.

Chadwick began a tour of the Manhattan Project facilities in November 1943, except for the Hanford Site where plutonium was produced, which he was not allowed to see. He became the only man apart from Groves and Oppenheimer to have access to all the American research and production facilities for the uranium bomb.

Observing the work on the K-25 gaseous diffusion facility at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, Chadwick realised how wrong he had been about building the plant in wartime Britain. The enormous structure could never have been concealed from the Luftwaffe.

Over the next two years, the Combined Policy Committee met only eight times. The first meeting on 8 September 1943, established a Technical Subcommittee. James Chadwick, the head of the British Mission to the Los Alamos Laboratory, was nominated to be a part of the Subcommittee along with Groves’ scientific advisor, Richard C. Tolman. It was agreed that the Technical Committee could act without consulting the Combined Policy Committee whenever its decision was unanimous.

Chadwick ensured that British participation in the Manhattan Project was complete and wholehearted. With Churchill’s backing, he attempted to ensure that every request from Groves for assistance was honoured. James Chadwick surprised everyone by earning the almost-complete trust of project director Groves, Jr.

Chadwick endeavoured to place British scientists in as many parts of the project as possible in order to facilitate a post-war British nuclear weapons project to which Chadwick was committed. Requests were made by Groves, via Chadwick, for particular scientists to support the project. The British scientists arriving in America accelerated in the early months of 1944. The British team was going to be critical to the Project’s success.

Chadwick arranged for Niels Bohr to visit the US in December 1943. Bohr didn’t remain at Los Alamos. He made a number of extended visits over the next two years, but his contribution was enough for Robert Oppenheimer to credit him with acting “as a scientific father figure to the younger men”. Oppenheimer also gave Bohr credit for an important contribution to the work on modulated neutron initiators. “This device remained a stubborn puzzle,” Oppenheimer noted, “but in early February 1945 Niels Bohr clarified what had to be done.”

Bohr recognised early that nuclear weapons would change international relations. In April 1944, he received a letter from Peter Kapitza, a leading Soviet physicist, inviting him to come to the Soviet Union. The letter convinced Bohr that the Soviets were aware of the Anglo-American project, and would strive to catch up. He sent Kapitza a non-committal response, which he showed to the authorities in Britain before posting.

Bohr met Churchill on 16 May 1944, but found that they were not of the same minds. In a letter to Winston Churchill, Niels Bohr describes the immensity and success of the Manhattan Project in the US. Bohr also conveys to Churchill that British and American scientists were working together harmoniously to produce an atomic weapon. Finally, Bohr warns of the future change that could occur in international relations and competition due to the creation of nuclear weapons.

Churchill disagreed with the idea of openness towards the Russians to the point that he wrote in a letter: “It seems to me Bohr ought to be confined or at any rate made to see that he is very near the edge of mortal crimes.”

Oppenheimer suggested that Bohr visit President Franklin D. Roosevelt to convince him that the Manhattan Project should be shared with the Soviets in the hope of speeding up its results. Bohr’s friend, Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, informed Roosevelt of Bohr’s opinions, and a meeting between them took place on 26 August 1944. President Roosevelt suggested that he should return to the UK to gain British approval.

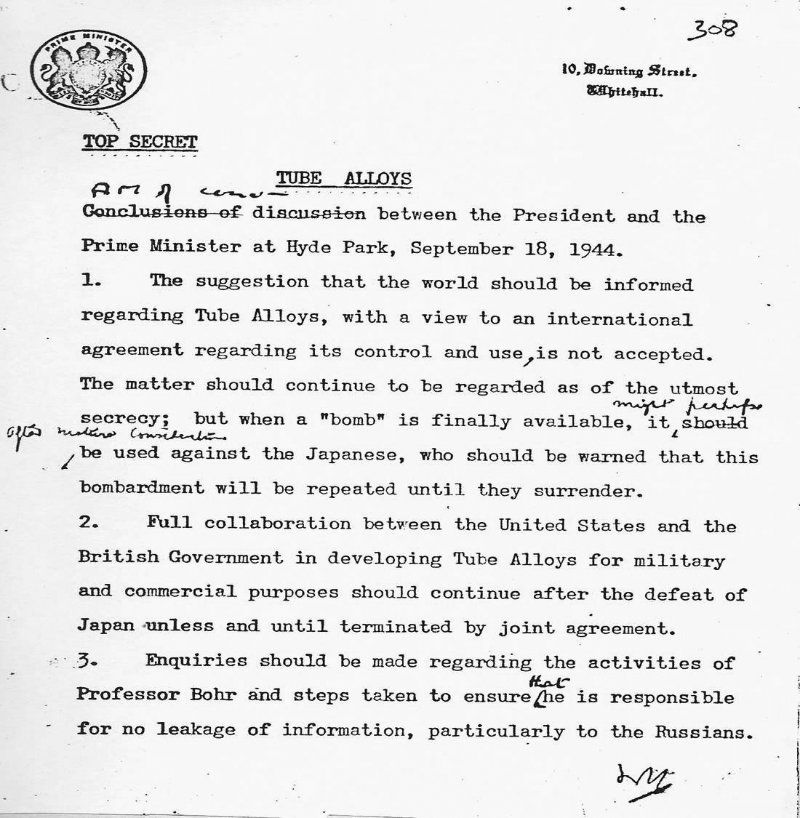

In September 1944, a second wartime conference was held in Quebec to discuss plans for the final assault on Germany and Japan. The conference was codenamed OCTAGON. After the conference, Churchill spent some time with Roosevelt at his estate in Hyde Park, New York. They discussed post-war collaboration on nuclear weapons. On 19 September they signed the Hyde Park Aide-Mémoire. The details of the agreement included the line – “Full collaboration between the United States and the British Government in developing Tube Alloys for military and commercial purposes should continue after the defeat of Japan unless and until terminated by joint agreement”. It also detailed the plan to use the bomb against Japan, and Churchill’s distrust of Niels Bohr.

Leahy knew of this secret wartime agreement. Leahy never believed that the atomic bomb would work, and was perhaps not paying much attention to the meeting, had only a muddled recollection of what had been said. When the Hyde Park Aide-Mémoire was raised in a Combined Policy Committee meeting in June 1945, the American copy could not be found. The UK sent a photocopy on 18 July. Even then, Groves questioned the document’s authenticity until the American copy was located many years later in the papers of Vice Admiral Wilson Brown, Jr., Roosevelt’s naval aide. The document was apparently misfiled in Roosevelt’s Hyde Park papers by someone unaware of what Tube Alloys was. They thought it had something to do with naval guns or boiler tubes.

In June 1950, Bohr addressed an “Open Letter” to the United Nations calling for international cooperation on nuclear energy. In the 1950s, after the Soviet Union’s first nuclear weapon test, the International Atomic Energy Agency was created along the lines of Bohr’s suggestion, and in 1957 he received the first ever Atoms for Peace Award.

Back at Los Alamos, 17 July 1944 – a meeting was held and it was agreed a gun-type bomb using plutonium was impractical. A few months earlier it was discovered the plutonium-239 produced by the Hanford reactors had too high a level of background neutron radiation. If such plutonium were used in a gun-type design, the chain reaction would start in the split second before the critical mass was fully assembled causing the weapon to pre-detonate and blow itself apart in what is known as a fizzle. The ‘Thin Man’ wasn’t to be.

High priority and almost all of the research at the Los Alamos Laboratory was moved to the development of the plutonium based ‘Fat Man’ bomb – the implosion-type weapon. This was a far more difficult engineering task.

All gun-type work in the Manhattan Project was directed at the ‘Little Boy’ bomb. ‘Little Boy’ was a development and simplification of the ‘Thin Man’. Like the ‘Thin Man’ bomb, it was to be a gun-type fission weapon. The difference was its explosive power was produced from the nuclear fission of uranium-235, whereas ‘Thin Man’ was based on fission of plutonium-239.

In late 1944, Los Alamos started to move from research to development and bomb production. Increased production at Oak Ridge and Hanford showed promise of enough plutonium and enriched uranium for the bombs.

With the successful Allied landings in France on D-Day, 6 June 1944, the war in Europe appeared to be entering its final phase. Germany was no longer the intended primary target. Intelligence indicated that the German atomic program had not gone beyond the research phase. General Groves and his advisers turned their sights to Japan. The challenge was on, to complete the atomic bomb in time to end the war in the Pacific.