Britain’s Nuclear Deterrent Development – Part Two

Photograph taken from a Japanese plane during the torpedo attack on ships moored on both sides of Ford Island shortly after the beginning of the Pearl Harbor attack. View looks about east, with the supply depot, submarine base and fuel tank farm in the right centre distance.

With thanks to the Vulcan to the Sky Trust www.vulcantothesky.org for kind permission to republish this series of blogs.

On 2 August 1939, the US President, Franklin D. Roosevelt, received a letter written by Leó Szilárd, a Hungarian-German-American physicist and inventor who conceived the nuclear chain reaction in 1933 and patented the idea of a non-fission nuclear reactor in 1934. The letter was signed by Albert Einstein, and warned that Germany might develop atomic bombs and suggested that the United States should start its own nuclear program.

The Einstein–Szilárd letter prompted action by Roosevelt. He called on Lyman Briggs to head the Advisory Committee on Uranium to investigate the fission of uranium. Briggs was an American engineer, physicist and administrator, and was a director of the National Bureau of Standards during the Great Depression of the 1930’s. Briggs was aged 65, when he was called into action for his new role as Chairman of the Uranium Committee.

Despite his influence, Einstein didn’t go on to work on the American nuclear programme. In July 1940, he was denied the work clearance needed, with the reasoning that his pacifist leanings and celebrity made him a security risk. It’s reported that Einstein later regretted signing the letter because it led to the development and use of the atomic bomb in combat. Einstein had justified his decision at the time because of the greater danger that Nazi Germany would develop the bomb first. In 1947 Einstein told Newsweek magazine that “had I known that the Germans would not succeed in developing an atomic bomb, I would have done nothing.”

The first meeting of the Advisory Committee on Uranium was held on 21 October 1939 and the committee reported to the President on 1 November 1939. While acknowledging that the science was unproven and that nuclear chain reaction was no more than a theoretical possibility, it foresaw that nuclear energy might be used as propulsion for submarines, and that an atomic bomb “would provide a possible source of bombs with a destructiveness vastly greater than anything now known.”

The Advisory Committee on Uranium was the beginning of the US government’s effort to develop an atomic bomb. Although the American President had sanctioned the project, progress was slow and was not directed exclusively towards military applications. Leó Szilárd believed that the project was delayed for a least a year by the short-sightedness and sluggishness of the authorities. At the time Briggs was not well and was due to undergo a serious operation. He was unable to take the energetic action that was often needed.

August 1941 – Some two months after the publication of the British MAUD report, Mark Oliphant, the man responsible for bringing the Otto Frisch and Rudolf Peierls paper to light, and an original member of the resulting MAUD committee, flew to the United States. The purpose of his visit was to supposedly discuss the radar programme, but he was actually assigned the task of finding out why the US was ignoring the MAUD Committee’s findings.

Oliphant reported that “The minutes and reports had been sent to Lyman Briggs, who was the Director of the Uranium Committee, and we were puzzled to receive virtually no comment. I called on Briggs in Washington, only to find out that this inarticulate and unimpressive man had put the reports in his safe and had not shown them to members of his committee. I was amazed and distressed.”

Oliphant then met with members of the Uranium Committee, William D. Coolidge, Samuel K. Allison, Ernest O. Lawrence, Enrico Fermi (who became the creator of the world’s first nuclear reactor) and James B. Conant to explain the urgency. He was also able to meet with Vannevar Bush, the director of the Office of Scientific Research and Development. In the meetings he spoke of an atomic bomb with forcefulness and certainty. Allison recalled that when Oliphant met with the committee, he “came to a meeting, and said ‘bomb’ in no uncertain terms. He told us we must concentrate every effort on the bomb and said we had no right to work on power plants or anything but the bomb. The bomb would cost $25 million, he said, and Britain did not have the money or the manpower, so it was up to us.” Allison was surprised that Briggs had kept the committee in the dark.

9 October 1941 – Vannevar Bush took the MAUD report directly to President Roosevelt and Vice-President Henry A. Wallace. They committed to an expanded and expedited American atomic bomb project. Two days later, Roosevelt sent a letter to Churchill in which he proposed that they exchange views “in order that any extended efforts may be coordinated or even jointly conducted.”

Leo Szilard later wrote, “if Congress knew the true history of the atomic energy project, I have no doubt but that it would create a special medal to be given to meddling foreigners for distinguished services, and that Dr Oliphant would be the first to receive one.”

Meanwhile, back in Britain the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research had already set up the Directorate of Tube Alloys to begin work on creating the Atomic Bomb. While Churchill’s response to Roosevelt’s letter assured him of a willingness to collaborate, there were concerns about the security of the American project. Britain also had concerns about what might happen after the war if the Americans embraced isolationism, as had occurred after the First World War, and Britain had to fight the Soviet Union alone. The British and American exchange of information was to continue but the programmes remained separate.

7 December 1941 – The Japanese attack on US naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, led to the United States entering World War II.

Funding now became available in significantly higher amounts than the year before. The American effort increased rapidly and soon outstripped the British, partly due to the American authorities’ reluctance to share details with their British counterparts. Several of the key British scientists visited the US early in 1942. They were given full access to all of the information available and were astounded at the momentum that the American atomic bomb project had gathered.

June 1942 – As the scale of the project became clearer in the US, the work of fission research was taken over by the United States Army Corps of Engineers, based in Manhattan. Brigadier General Leslie R. Groves, Jr. became the director of the Manhattan Project and attempted to tighten security through a policy of strict compartmentalisation similar to the one that the British had imposed on radar.

On 30 July 1942, Churchill was advised that Britain’s pioneering work was a dwindling asset and should be capitalised on quickly before all was lost. But, by the time Britain’s need for a merger was realised, the US decided that outside help for the Manhattan Project was no longer needed.

Summer 1942 – To combat the slow progress of the Tube Alloys project, Hans von Halban and his Cambridge team of scientists were transferred to Canada. Halban was to be the head of the research laboratories at the Montreal Laboratory. This group would later go on to develop one of the first heavy water reactors in the world, at Chalk River Laboratories.

In October 1942, Roosevelt was convinced by his team that the United States should independently develop the atomic bomb. Access was restricted to classified information which Britain could use to develop its atomic weapons programme, even if it slowed down the American efforts.

The Americans stopped sharing any information on heavy water production, the method of electromagnetic separation, the physical or chemical properties of plutonium, the details of bomb design, or the facts about fast neutron reactions. This hindered the work of the British and the Canadians, who were collaborating on heavy water production and several other aspects of the research programme at the Montreal Laboratory.

By 1943 Britain had stopped sending its scientists to the United States, which slowed down the pace of work there as they had relied on efforts led by British scientists. In March 1943 the US decided that Britain’s help would benefit some areas of the Manhattan Project. In particular James Chadwick, William Penney, Rudolf Peierls and Mark Oliphant were important enough that the bomb design team at the Los Alamos Laboratory needed them. Important enough to warrant the risk of revealing weapon design secrets.

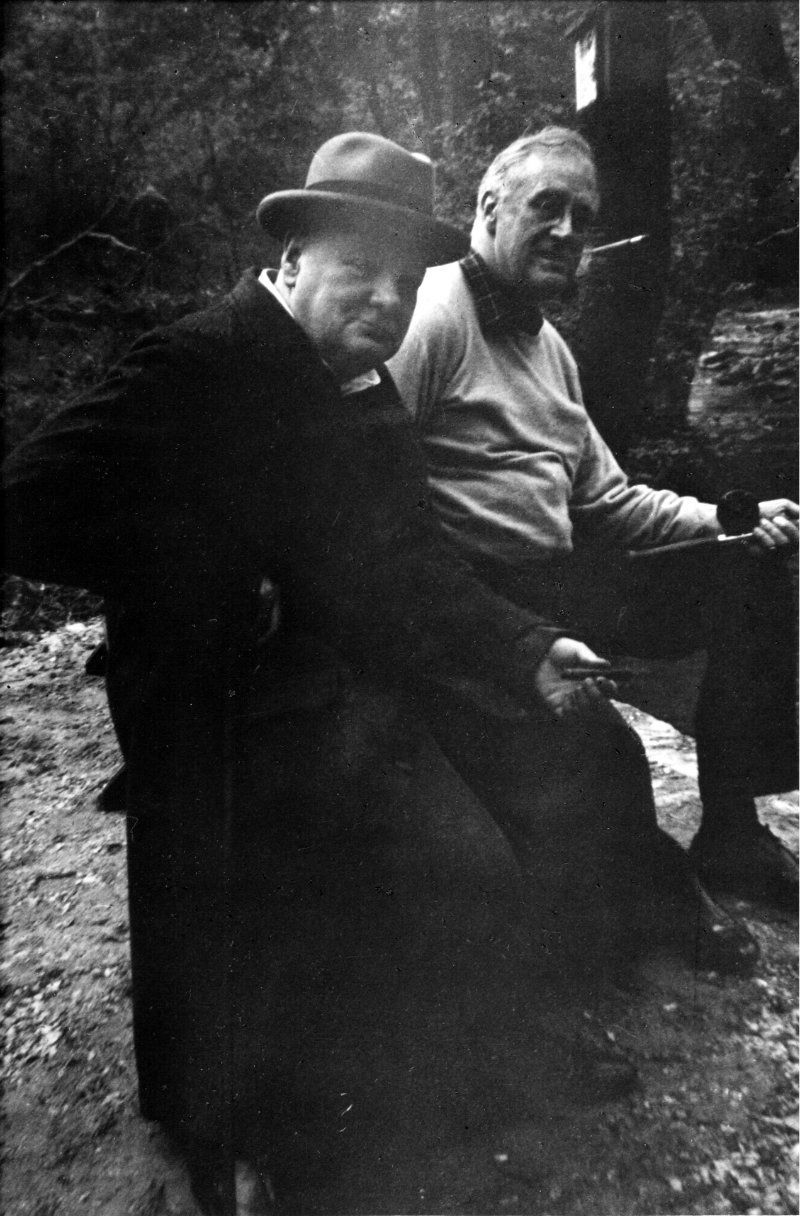

Churchill raised the matter with Roosevelt at the Washington Conference (codenamed Trident) on 25 May 1943. The conference was a World War II strategic meeting between the UK and the US, but became an opportunity to address the situation of the sharing of information. They agreed that information interchange should be reviewed, and that the atomic bomb project should be a joint one.

Churchill proposed a five point agenda for collaboration:

- a free exchange of information should occur between the two nations

- an agreement to not use the bomb against each other

- an agreement to not use the bomb against other nations without consent of both

- an agreement not to share information with other parties without the consent of both

- the United States could have full use of British commercial and industrial capacities.

Churchill had a profound influence on President Roosevelt, and despite resistance from United States advisors such as Vannevar Bush and James Conant, the two leaders agreed to collaborate.

On 19 August 1943, at the First Quebec Conference in Quebec City, Churchill and Roosevelt signed the Quebec Agreement. The Quebec Conference (codenamed Quadrant) was to discuss the invasion of France, but a speedy drafting process was achieved to complete the Quebec Agreement. The agreement adopted most of Churchill’s five point plan and merged the British Tube Alloys project with the American Manhattan Project. The agreement also established a Combined Policy Committee, with representatives from the US, the UK, and Canada to control the joint project. Importantly, the agreement gave the Manhattan Project the resources of British uranium, an established research centre in Montreal, and ensured the participation of British scientists.

The Quebec Agreement was a secret agreement. Its terms were known only to a few insiders, and its existence was not revealed to the United States Congress. The Joint Committee on Atomic Energy in the US was given an oral summary, but not until 12 May 1947. On 12 February 1951, Churchill wrote to the President at the time, Harry S. Truman, for permission to publish it. Truman declined and Churchill omitted it from his memoir, Closing the Ring. It remained a secret until Churchill read it out in the House of Commons on 5 April 1954, during debate on the hydrogen bomb.

After the signing of the Quebec Agreement, many prominent British scientists were soon transferred to the United States to work on the Manhattan Project. The head of the British Mission to the Los Alamos Laboratory, James Chadwick, led the team, which included Rudolf Peierls, Klaus Fuchs (later revealed to be a Soviet atomic spy), Mark Oliphant and William Penney. The Los Alamos Laboratory was also known as Project Y and was a secret laboratory established by the Manhattan Project.