A note from the BNTVA Curator.

I have made the decision that I wanted to reshare this fantastic blog the Ceri wrote last year and to update it with some better quality photos. Since this was first written I have found some more photos from Operation Mosaic that were in an old BNTVA archive box which had been passed on to me last summer. Some of the photos were initially unattributed but further research has identified the veteran they came from.

(Something I endeavour to do with all photos that have been previously passed to the BNTVA)

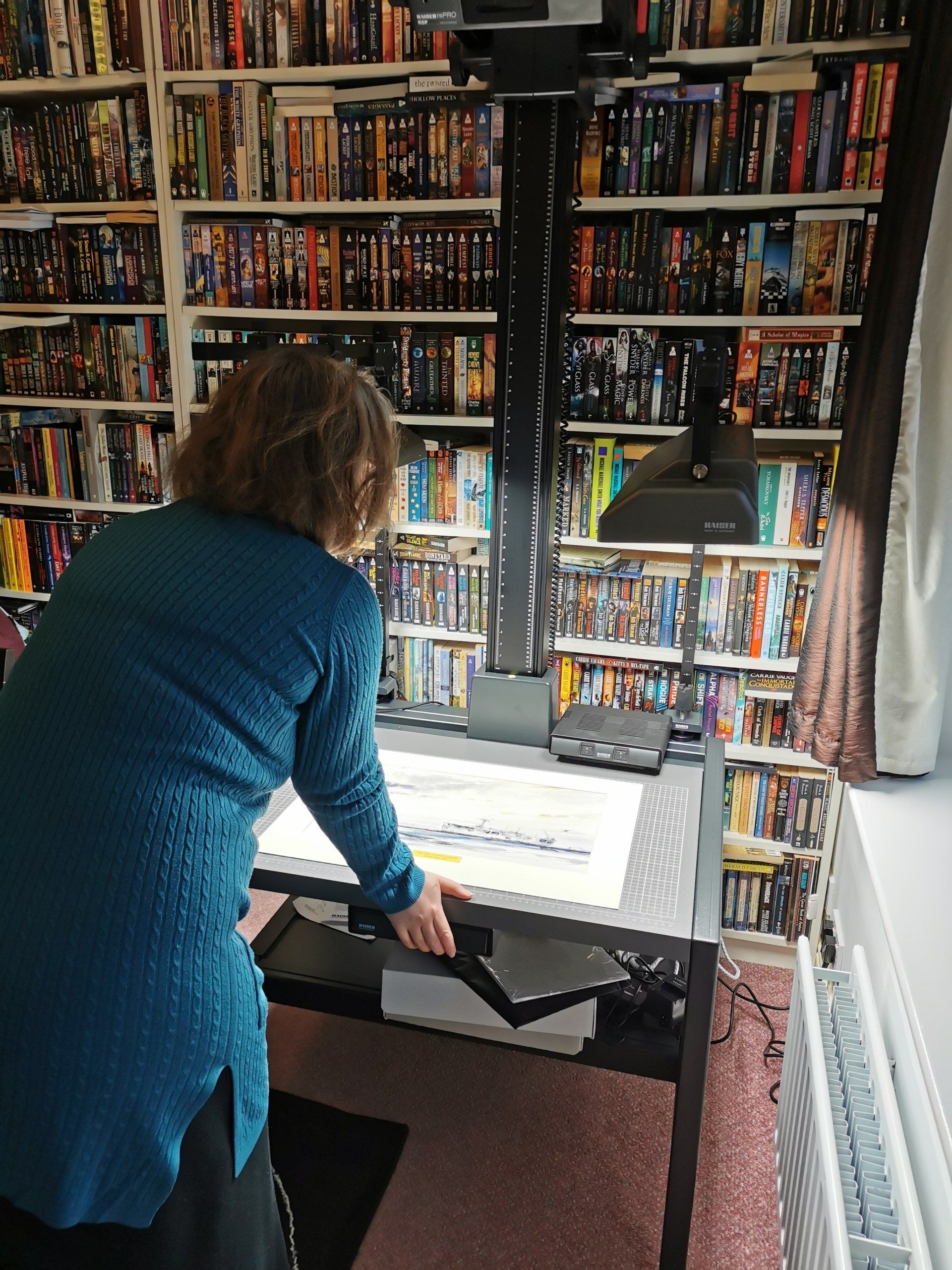

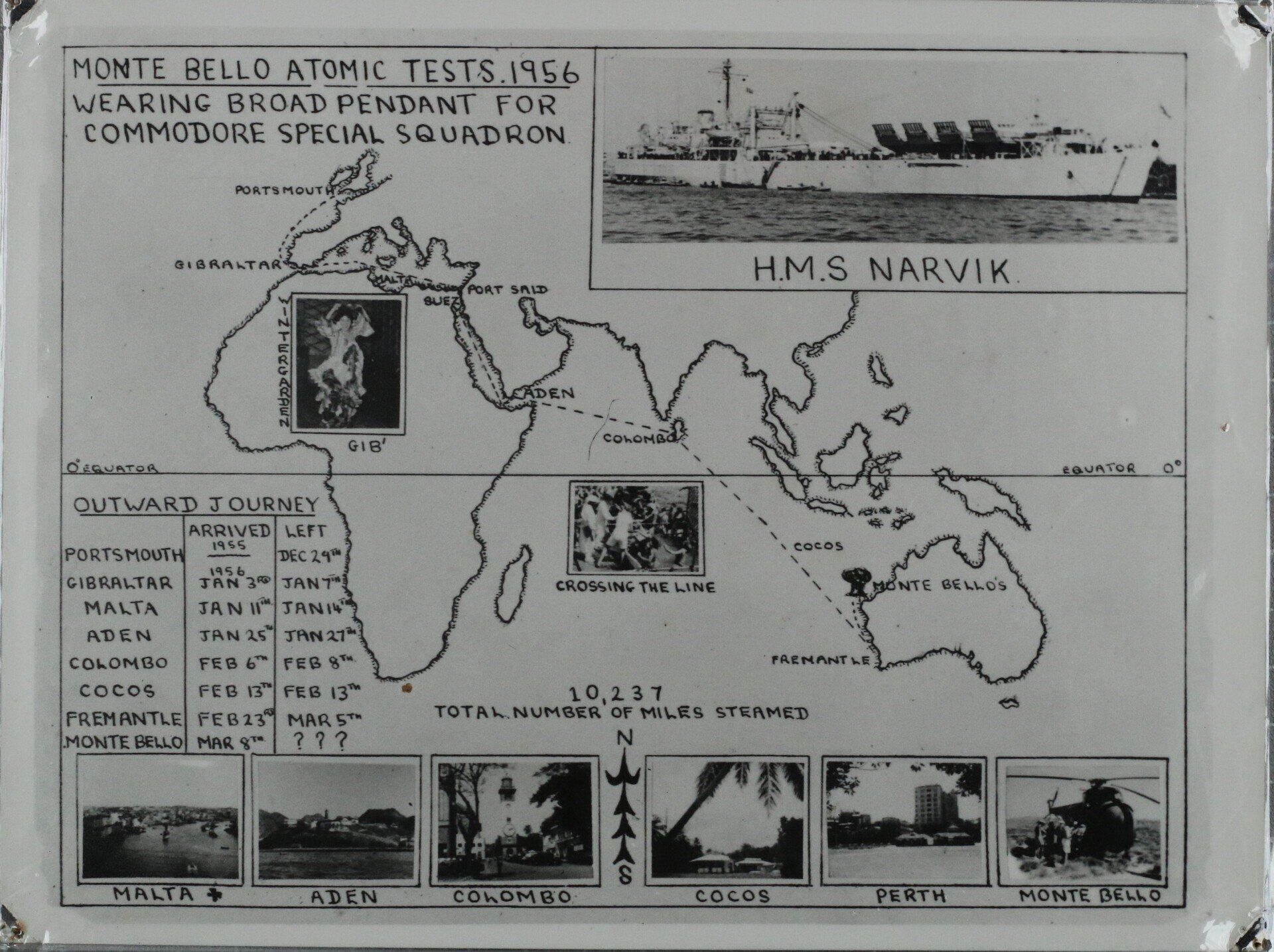

We have found more documentation about the tests, and at the 2021 BNTVA Conference, Roger Grace kindly allowed me to take his amazing photo album away so we could professionally digitise the photos on our copy stand. We previously used some of Rogers photos in this blog so it is great to be able to show them off better! They are one of the best collection of photos from Operation Mosaic I have seen so far.

Please note that I am still actively hunting for more material from Operation Mosaic including the films that were made, so far I've only located the rushes at the IWM.

I want to just finish with a thank you to everyone who has contributed to the BNTVA Collections & Archives, whether its your written accounts, oral histories or photos and ephemera, because without your assistance we can't tell your stories.

Thank You,

Wesley Perriman

BNTVA Curator

The beginning of Operation Mosaic – why did British nuclear testing return to the Montebello Islands? by Ceri McDade

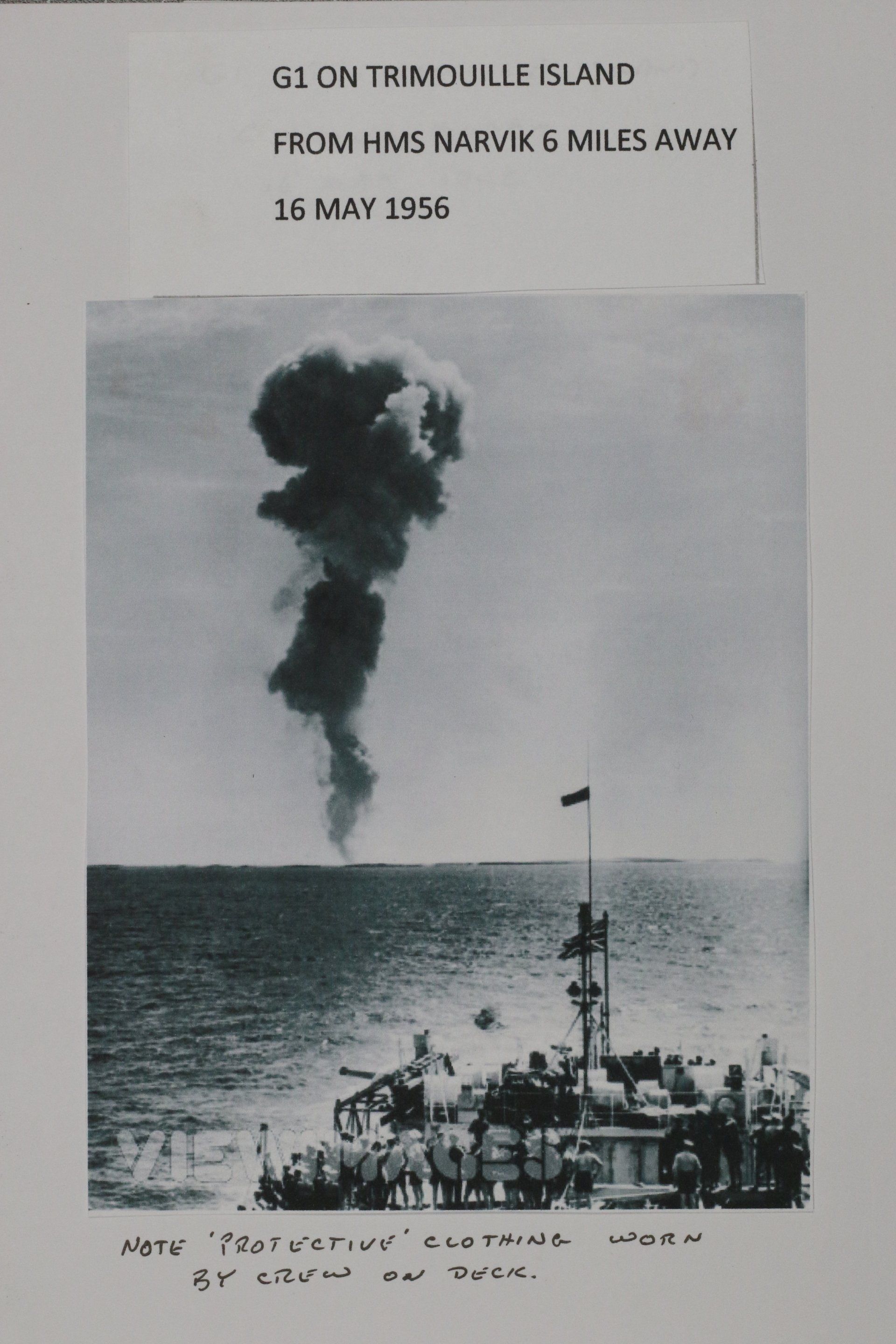

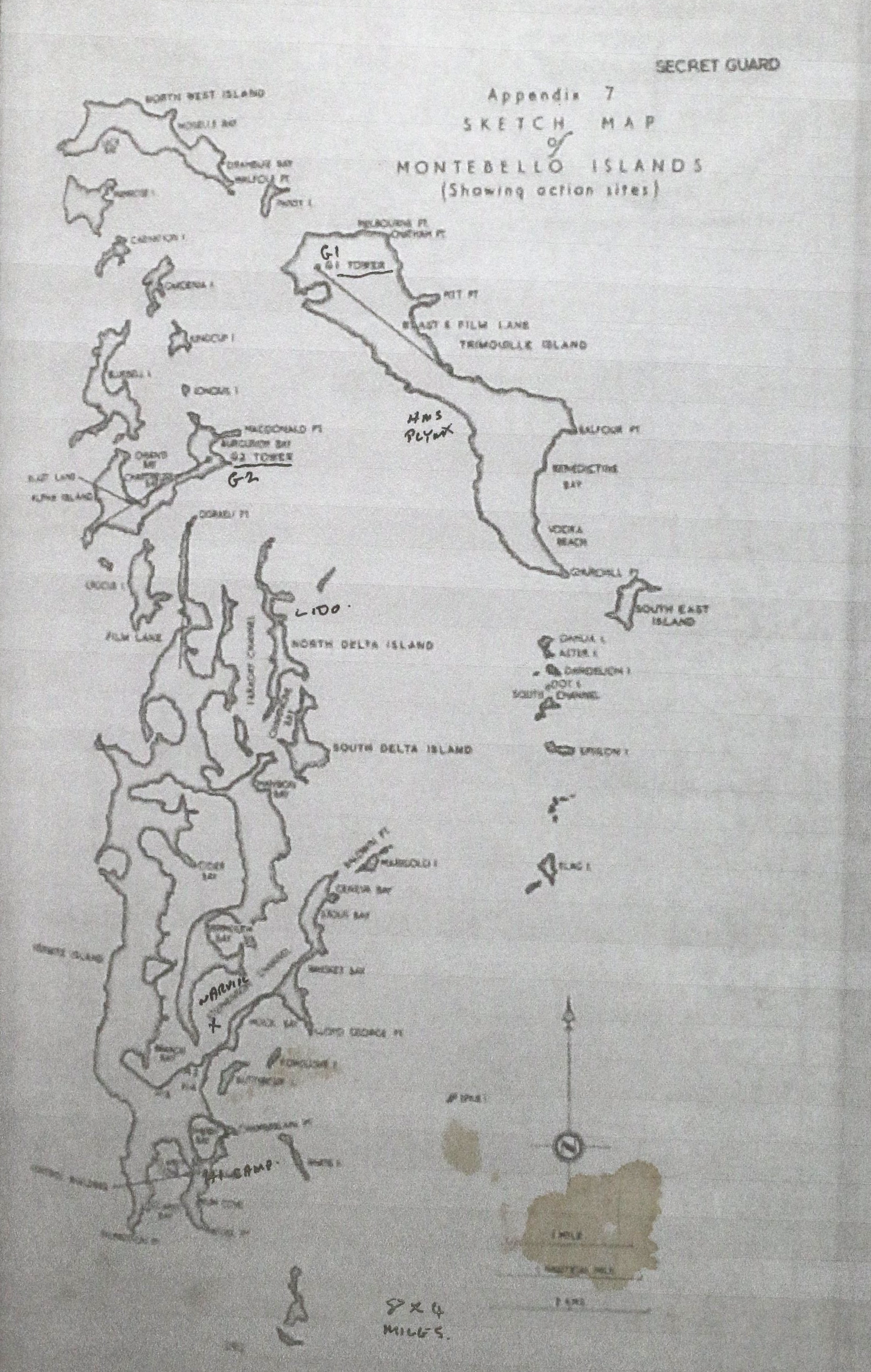

Operation Mosaic was a series of two British nuclear tests conducted at the Montebello Islands on 16 May and 19 June 1956; this blog post explores G1, the first lower yield test of 15kt, detonated on 16 May 1956 at 1150 hours. The Maralinga testing site was not yet ready, so the Montebello Islands were chosen as the perfect place to perform these two tests.

The purpose of G1 was to test the increased yield of British nuclear weapons and is set in time at the Montebello Islands three and a half years after Operation Hurricane, the first British 25-kt atom bomb test aboard the HMS Plym on 3 October 1952. The British then performed Operation Totem in October 1953, which tested a limit on the amount of plutonium-40 that could be present on a bomb. Alongside Totem, which took place at Emu Field in the Great Victoria Desert in 1953, were the Kittens trials, which didn’t focus on explosions, but experimented with the effects of conventional explosives on polonium-210, beryllium and natural uranium to investigate “neutron initiators”, which kick start a fission chain reaction. These “Minor Trials” at Emu Field became known for causing more destructive damage than the major tests a couple of years later. The British weren’t keen on returning to Emu Field due to the sudden dust storms, sand dunes and water shortage which could hamper their time-constrained work on competing with the US to test a British hydrogen bomb.

It was clear that the British scientists, under William Penney, were becoming more ambitious in their testing, focusing on output and competition with the US rather than the safety of military personnel. The Atomic Weapons Research Establishment (AWRE) considered using boosted fission weapons, where isotopes of light elements such as lithium-6 and deuterium were added. They had heard from the American tests, that using a natural uranium tamper (uranium-238 can be used during fission to produce plutonium-235) could increase the yield from 20-50%. The Australian government had already dictated that the British were not allowed to experiment with hydrogen bombs in Australia, so using a boosted fusion weapon, circumvented the fact that they would test a hydrogen bomb, despite it being closely linked with hydrogen bomb development.

Prime Minister Anthony Eden cabled Robert Menzies, Prime Minister of Australia, on 16 May 1955, to detail the proposed tests. Eden promised that the yield would be less than two and a half times the yield of Operation Hurricane, hence not exceeding around 60kt of TNT; later 80kt was agreed between Eden and Menzies. Eden stated that the two bombs would be detonated from towers and would produce a fifth of the fallout from Operation Hurricane in 1952; he gave assurances that there would be no harm to sea life or animals and humans on mainland Australia.

Both G1 and G2 became the responsibility of the Royal Navy. Planning took place from February 1955 under codename Operation Giraffe before the Admiralty adopted the name Operation Mosaic in June 1955. The scientific director, Charles Adams from AWRE, had deputised for William Penney at Operation Totem, with Ieuan Maddock as scientific superintendent. Group Captain S W B (Paddy) Menaul commanded the Air Task Group. Menaul was already a British nuclear test veteran, as he had been an observer on board Vickers Valiant WZ366, when it had made its first operational drop of a British atomic bomb at Operation Totem, Emu Field.

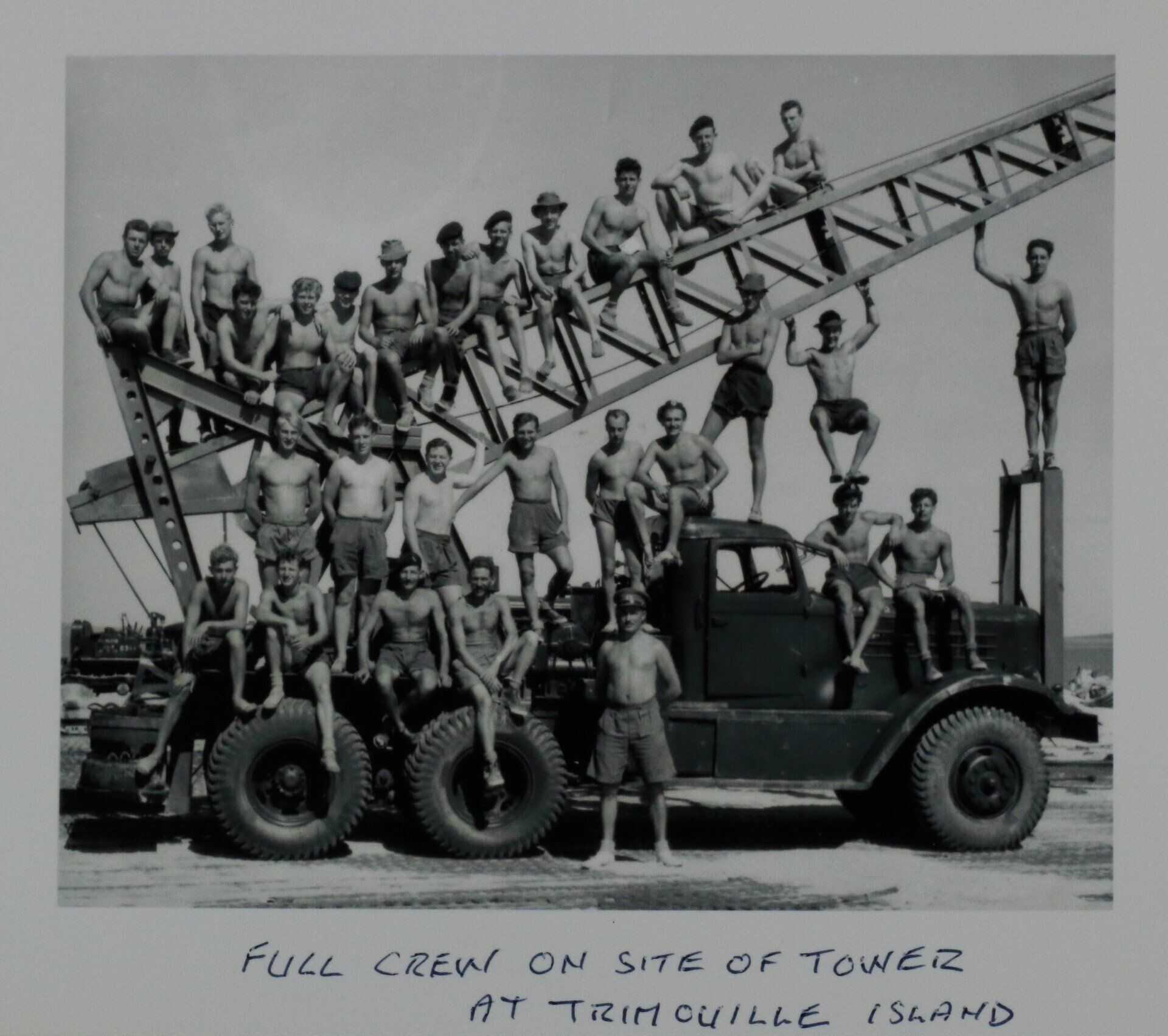

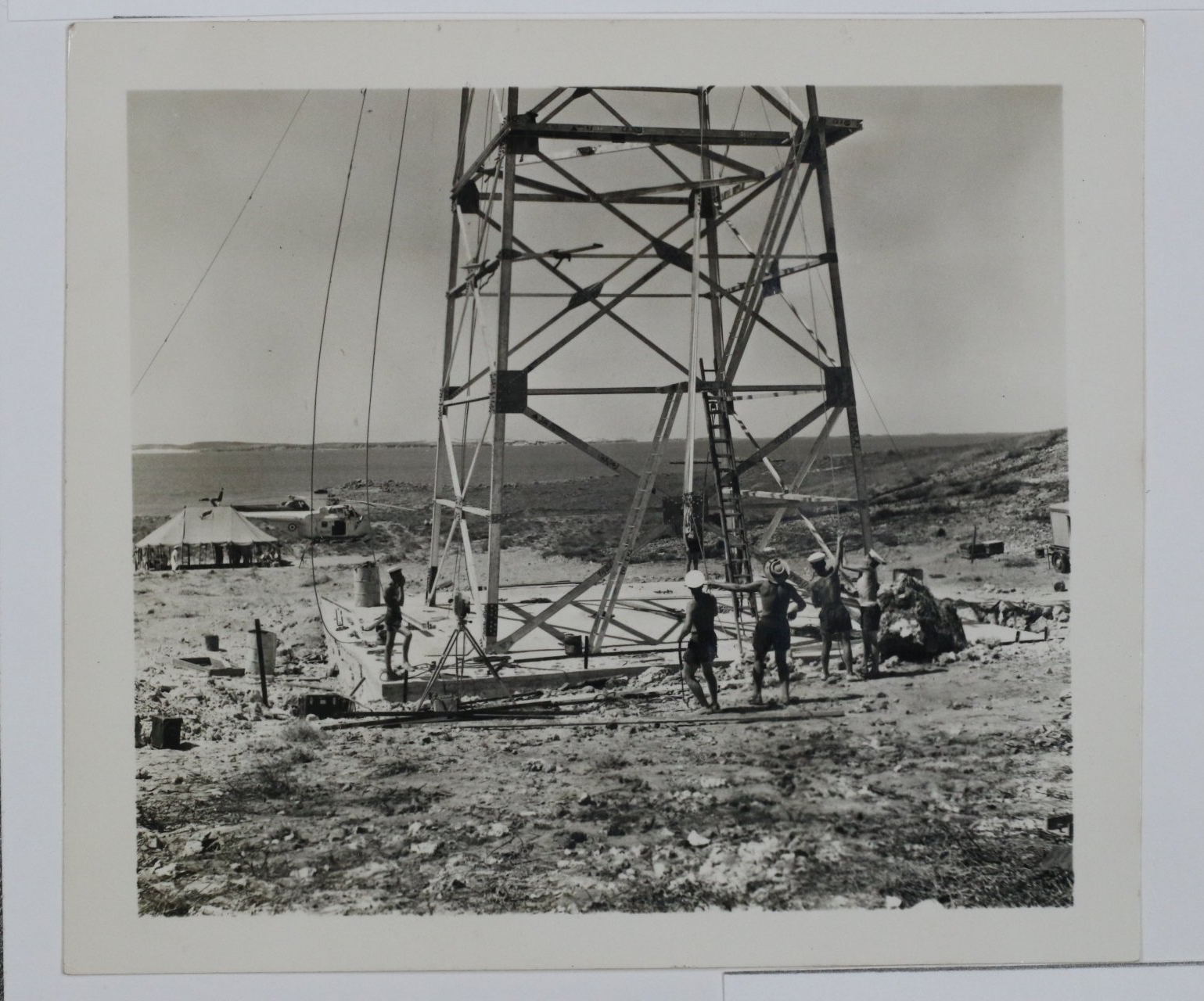

The Australian government formed a Montebello Working Party as a subcommittee of the Maralinga Committee set up for the future tests from September 1956 in South Australia. The HMAS Warrego (sloop) and Karangi (boom defence) conducted mooring, hydrographic surveying and marking operations of marker buoys for moorings in October and November 1955. Site preparations, including construction of the two 300ft towers, were performed by the Royal Engineers. The Royal Engineers and Royal Navy built a shore camp, control building and camera tower on Hermite Island, and weapons towers on Trimouille and Alpha Islands. A naval meteorological station was set up at Christmas Island, along with operational bases at Onslow, Pearce and Darwin, Australia. The corvettes HMAS Fremantle and Junee provided logistical support, ferried personnel between islands and housed the designated 14 British and Australian media representatives during G1.

HMS Alert, HMS Narvik and RFA Eddyrock formed Task Force 308.1. Captain Hugh Martell took charge as commander of Task Force 308 from the HMS Narvik. The Royal Australian Navy component comprised HMAS ships Junee, Fremantle, Karangi, MRL 252 and MWL 251, which were anchored 12 miles southeast of Ground Zero and were named Task Group (TG) 308.2. The HMS Newfoundland, along with destroyers HMS Cossack, Consort, Concord and Comus formed Task Force 308.3; the HMS Diana was detailed to perform scientific tests for G2 in Task Force 308.4.

Leslie Martin (Australian physicist and member of the Australian Atomic Energy Commission)), Ernest Titterton (British nuclear physicist who researched under Mark Oliphant), Cecil Eddy, W A S Butement (of the recently formed Atomic Weapons Tests Safety Committee, AWTSC) and L J Dwyer were flown from Onslow to the HMS Narvik on 14 May 1956. Martell set the date of the test for the 16 May on 15 May. This was a tentative time as the AWTSC didn’t initially approve the test. Penney sent a message to Adams on 10 May, and the test was back on. Four RAF Canberra bombers flew from Pearce – two conducted cloud sampling (one flown by Menaul) around 20 minutes after firing, whilst two provided support.

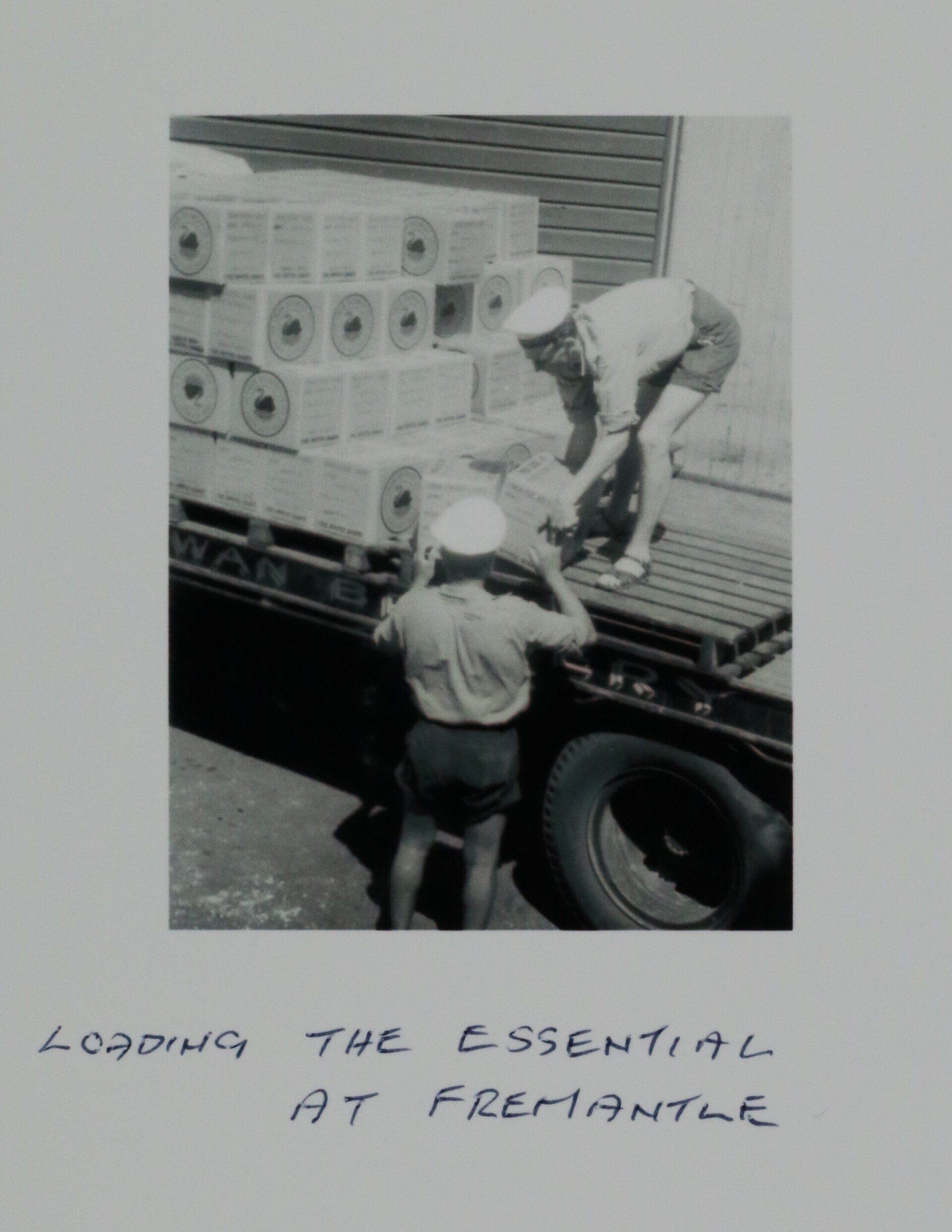

The RFA Eddyrock (an Eddy Class Fleet Attendant Oiler, A198) arrived at Fremantle on 5 April 1956 to load cargo and stores for the ships at the Montebello Islands for G1, which she also took part in.

Rehearsals were held on 27 April and 2 May, followed by a full rehearsal on 5 May. The fissile material was delivered by an RAF Hastings to Onslow, and collected by the HMS Alert on 11 May, delivered the next day to the Montebello Islands. The G1 test was detonated from a tower on the northwest of Trimouille Island.

MWL 251’s commanding officer, Lieutenant George Halley, described the blast,

“At 1145 all the hands mustered on the port side of the boat deck and the countdown commenced at 1148… At 1151, although we had our backs to Trimouille Island, we experienced a blinding flash of intense magnitude, followed by a slight burning feeling across the back of the neck and at the back of the knees. This was only momentarily (sic) and the intensity of the heat resembled the warmth of the sun on a December day. At ‘H’ plus 5 seconds, the hands were permitted to face the direction of Trimouille Island. On looking round we observed the last stages of the fireball. It resembled a huge oil fuel fire. As soon as it had contracted a thick mass of dark grey cloud rose in a vertical direction at a terrific speed. The familiar mushroom cloud soon developed. Shortly afterwards at approximately H plus 60 seconds, the blast wave was felt, company turned towards Alpha Island and on this occasion the glare of the fireball seemed to last longer and was more intense in its magnitude.”

After detonation at 1150 on 16 May, HMS Narvik and Alert entered the Parting Pool; the Radiological Group wore full protective clothing and entered the lagoon in a cutter, conducting a survey and retrieving instruments. A decontamination tent with a pumped water supply allowed the group to wash themselves before returning to the HMS Narvik. The ship’s evaporators weren’t run due to fear of radioactive contamination. A Varsity aircraft surveyed the Onslow to Broome coastline one day after G1’s detonation and reported there was no radiation. Maddock visited the crater on 25 May to take soil samples and collect film badges from Hermite Island.

The Canberra bombers were monitored and decontaminated on their return to RAAF Pearce.

The results of the test showed a yield between 15-20kt of TNT, which had been anticipated, however the cloud rose to 21,000ft rather than the predicted 14,000 ft. Although the implosion system had performed perfectly, the boosting effect of lithium deuteride was negligible. The fallout moved out to sea, but then reversed direction across northern Australia. Radioactive contamination from G1 was found on aircraft at Onslow, indicating that fallout had indeed blown across mainland Australia.

Arnold, L. and Smith, M. (2006), Mosaic-1956, Britain, Australia and the Bomb, pp.106-137 https://springer.com/chapter/10.1057/9780230627338_7

I have included this film as it includes Roger Grace speaking about his experiences and finishes with looking at the G1 test from the deck of HMS Narvik.